Information about Eye Conditions, Diseases, and Vision Care

What is visual acuity?

Visual acuity is the medical term for sharpness of vision. Refractive errors, which can be corrected with eyeglasses, are the most common cause of poor visual acuity. These include myopia, or nearsightedness; hyperopia, or farsightedness; and astigmatism. Myopia is a reduced ability to see distant objects clearly, hyperopia is a condition that initially causes difficulty in seeing nearby objects and progresses to affect distance vision, and astigmatism is blurred vision caused by abnormal curvature of the front surface of the cornea.

How is visual acuity measured?

Overall visual acuity is measured by using the Snellen Eye Chart, with the large E at the top followed by rows of letters where each row is smaller than the previous one. A chart using the letter E facing up, down, left, and right is used for children and those who do not read.

For the test, the eye chart is placed 20 feet from the person being examined. For someone wearing eyeglasses, the test first is performed without glasses. One eye is covered, and the person reads the lowest line on the chart that can be ascertained. Then the same procedure is followed to test the other eye. Last, the sequence is performed while the eyeglasses are worn.

A reading of 20/20 is normal vision, meaning that the smallest symbol that can be read at a distance of 20 feet is the same as the symbol that a person with normal vision would detect at that distance. A 20/40 reading means that the person can read at a distance of 20 feet what a person with normal vision reads at 40 feet. A person whose vision can be corrected to 20/200 vision in the better eye is considered legally blind.

Near visual acuity is measured with the Jaeger card, which has print samples of different sizes. The card is held 14 inches from the person’s eye for the test. A result of 14/20 means that the person can read at 14 inches what someone with normal vision can read at 20 inches. The results of visual acuity tests are used to prescribe eyeglasses or other corrective measures.

Allergies occur when the body overreacts to often-harmless substances in the environment. Triggered by the body’s immune system, allergies protect eyes from injury. Because the eye is an exposed area of the body, foreign particles such as pollen, animal dander, and mold spores can adhere to the moist ocular surface and cause the same types of allergic reactions as generated when the particles reach the nose, throat, or lungs.

Although people with eye allergies often have hay fever or other allergic problems, sometimes the eye reaction can come as a complete surprise. Visible symptoms of eye allergies may include swelling, hives, itching, watering, redness, eye pain, and sensitivity to light. Symptoms of eye allergies are similar to symptoms of infectious diseases of the eyes, so diagnosing and treating ophthalmic allergic conditions can be a challenge.

What causes eye allergies?

Allergic reactions in the eyes, or ocular allergies, can be caused by airborne particles such as pollen, animal dander, dust, or molds. Eye allergies can be seasonal, or they may be perennial, affecting sufferers unpredictably throughout the year. Bacteria, food sensitivities, cosmetics, fabrics, soaps, and other substances may cause year-round allergies. Plant pollens and molds are the most common causes for chronic seasonal allergies. People who wear contact lenses can have ocular allergies to contact lens solutions as well as to the environment.

Airborne allergens can readily reach the conjunctiva, which is the thin, transparent membrane that lines the inner surface of the eyelid and covers the sclera where it becomes the white of the eye.

How do you protect your eyes from allergies?

The best way to protect your eyes from allergies is to avoid allergens completely. Some of the most common ones are cigarette smoke, cat dander, smog, some houseplants, and petroleum solvents. It’s important to determine the cause of allergies where possible. An allergist can administer a comprehensive battery of diagnostic tests.

The best way to protect your eyes from allergies is to avoid allergens completely. Some of the most common ones are cigarette smoke, cat dander, smog, some houseplants, and petroleum solvents. It’s important to determine the cause of allergies where possible. An allergist can administer a comprehensive battery of diagnostic tests.

You can apply ice packs and cold compresses over your eyes to provide relief from allergic reactions, thereby reducing puffiness and itching. Using a tear substitute helps to remove and dilute allergens, and you can use ointments and time-released tear replacements at night to moisturize the ocular surface. Applying a topical antihistamine reduces eye redness and itching. Mild topical steroids, which should only be used under a doctor’s supervision, can treat acute or chronic cases. Eyeglasses and facial hair can collect allergens, so clean them frequently. A facemask can often provide relief when you are outside, while special air filters, either freestanding or furnace-mounted, can minimize the allergens in the air inside your home.

Many allergies are seasonal, and the symptoms disappear for periods of time. However, every time your eye is inflamed, it never completely recovers. Allergies of the eye should be taken seriously and treated by an eye doctor to prevent more serious consequences.

Amblyopia, or lazy eye, is poor vision in an eye that failed to develop normal sight during early childhood. It is usually caused by a lack of use of that eye because the brain has learned to favor the other eye. To protect a child’s vision, amblyopia should be corrected during infancy or early childhood.

What types of amblyopia exist?

Any condition that affects normal use of the eyes and visual development can cause amblyopia. There are three major causes of amblyopia, and the condition is sometimes hereditary:

Strabismus is the most common cause of amblyopia and often occurs in eyes that are not aligned properly or are crossed. The crossed eye turns off to avoid double vision, and the other eye takes over most of the visual function. Because the brain favors one eye over the other, the nonpreferred eye is not adequately stimulated, and the brain cells responsible for vision in that eye do not mature normally.

Strabismus is the most common cause of amblyopia and often occurs in eyes that are not aligned properly or are crossed. The crossed eye turns off to avoid double vision, and the other eye takes over most of the visual function. Because the brain favors one eye over the other, the nonpreferred eye is not adequately stimulated, and the brain cells responsible for vision in that eye do not mature normally.- Refractive amblyopia is caused when the eyes have unequal refractive power. For instance, one eye may be nearsighted and the other farsighted. Amblyopia occurs when the brain cannot balance this difference and chooses the easier eye to use. The eyes appear normal but, because the brain is using only one eye most of the time, the other has poor vision. This type of amblyopia is hard to detect and requires careful measurement of vision.

- A third cause of amblyopia is any eye disease or injury that prevents a clear image from being focused inside the eye. For example, cataracts, which occur when the eye’s natural lens becomes cloudy, can cause amblyopia.

How is amblyopia detected?

Unless an eye is misaligned, amblyopia is not easily detected, especially in a child. Children are often not aware that they have one strong eye and one weak eye because their sight has been that way since birth. And, without obvious abnormalities, there is no way for parents to tell that a problem exists with the child’s vision. Therefore, you should schedule a comprehensive vision exam for your child to detect a difference in refractive power between the two eyes. Children should have their first exam by the age of 4. If you suspect any vision problems, if your child’s eyes appear misaligned, or if there is a family history of amblyopia, you should schedule an appointment for your child at a younger age.

How is amblyopia corrected?

Treating the cause alone cannot cure amblyopia. Treatment always requires forcing the brain to use the nonpreferred eye. Eye patching and vision therapy are the most effective means of treatment. By patching the normal eye for most or part of the day, often for weeks or months, the brain must use the weaker eye. To correct errors in focusing or to balance an unequal refractive power between both eyes, glasses may be prescribed. Vision therapy then trains the brain to use the eyes to work together.

Astigmatism is a vision disorder that occurs when the cornea of the eye is uneven in shape. More rarely, it can result from the way in which the eye’s natural crystalline lens refracts light. Either condition causes a distorted image to fall on the retina.

The human eye works much like a camera with two lenses — the cornea, which is a clear membrane that covers the front of the eye, and the natural crystalline lens, which is located behind the pupil. These two lenses work together to focus light on the retina, which is the membrane that covers the back two-thirds of the eye and works like the film in a camera. A normal cornea should be curved equally in all directions, allowing light to focus exactly on the surface of the retina. Most vision problems result from an irregularity in the curvature of the cornea or in the shape of the eye.

What causes astigmatism?

If the cornea is uneven in shape, the result is astigmatism, which causes light rays to be bent out of focus, either horizontally or vertically, resulting in distorted vision at all distances.

Astigmatism is prevalent and, in most cases, if you have it, you were born with it. Just as your hands are shaped differently from other people’s hands, so are your eyes. Eyelid swelling, corneal scars, and keratoconus, a rare condition that causes the cornea to be misshapen, can also cause astigmatism.

How do you know you have astigmatism?

Very mild astigmatism may cause no visual symptoms because the muscles of the eye will compensate for the uneven curvature of the cornea. If the eye has to work too hard to compensate, however, eyestrain and headaches can result. In addition, mild astigmatism can cause eye fatigue or blurry vision at certain distances. Severe astigmatism will usually cause distorted, double, or blurry vision.

An eye doctor detects astigmatism during the course of a regular eye examination.

How is astigmatism treated?

Astigmatism can be treated surgically or nonsurgically. Prescription eyeglasses and contact lenses or laser vision correction surgery correct most cases of astigmatism. The most prevalent nonsurgical correction is a prescription for rigid gas permeable (RGP) contact lenses. Because it is rigid, an RGP lens will fill in the irregular areas of the cornea with tears, creating a smooth spherical surface and correcting astigmatism. Special soft contact lenses called torics also compensate for the astigmatic shape of the corneas. In those cases where the astigmatism arises from the eye’s natural crystalline lens rather than the cornea, a special bitoric contact lens may be prescribed. It offers refracting surfaces on the front and back to correct the problem in much the same way that eyeglasses do.

If you are contact lens-intolerant or just want to be free from glasses or contacts, you may opt to have some form of vision correction procedure performed by a qualified eye surgeon. LASIK, the most popular form of laser vision correction, can provide correction for relatively high degrees of nearsightedness and astigmatism as well as some cases of farsightedness and astigmatism.

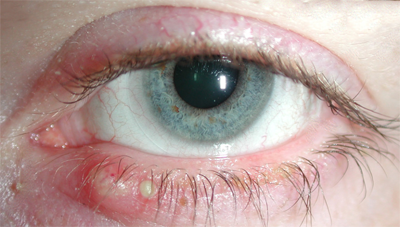

Blepharitis is an inflammation of the eyelids that can affect persons of all ages. Excess oil is produced in the glands near the eyelid, which creates a favorable environment for the growth of bacteria. It is a common condition that has multiple causes. The three most prevalent forms of this condition are seborrheic, staphyloccocal, and mixed. Another less common, but severe form of blepharitis, is ulcerative blepharitis.

Blepharitis is an inflammation of the eyelids that can affect persons of all ages. Excess oil is produced in the glands near the eyelid, which creates a favorable environment for the growth of bacteria. It is a common condition that has multiple causes. The three most prevalent forms of this condition are seborrheic, staphyloccocal, and mixed. Another less common, but severe form of blepharitis, is ulcerative blepharitis.

Seborrheic blepharitis, the least severe and most common form, is often associated with dandruff of the scalp or acne-like skin conditions. It is a dysfunction of a type of gland that exists in the eyelid and the skin. This type of blephartis usually affects the mature population and appears as greasy flakes or scales around the base of the eyelashes and as a mild redness of the eyelid. Symptoms are itchiness, foreign body sensation, discharge, and burning.

Staphylococcal blepharitis is an infection of the eyelids and commonly begins in childhood, continuing throughout adulthood. Invading bacteria cause inflammation of the eyelids and produce irritants and bacteria toxins that are harmful to the eye. Crusting, scaling, hair losses, chronic redness, and whitening of lashes are common symptoms. Treatment is most important to prevent potential scarring of the cornea and conjunctiva.

Mixed blepharitis is a combination of both seborrhea and staphyloccocal forms of this condition, and symptoms of both types can appear.

Ulcerative blepharitis is characterized by matted, hard crusts around the eyelashes that result in small sores that may bleed or ooze when removed. Loss of eyelashes, distortion of the front edges of the eyelids, and chronic tearing may also occur. The cornea may also become inflamed.

In any form of blepharitis, the conjunctiva and cornea can be affected. Even mild conditions can be uncomfortable and unattractive, and if untreated, can lead to more serious problems. Complications – such as prolonged infection, injury to the eye tissue from irritation (corneal ulcer), inflammation of the conjunctiva, loss of eyelashes, and scarring of the eyelids – may occur.

How is blepharitis controlled?

Good eyelid hygiene is essential in treating blepharitis. Warm, moist compresses can also help relieve symptoms when used in conjunction with regular eyelid cleansing. Because staphylococcal blepharitis is an infection, antibiotics and/or corticosteroids can treat the infection and help reduce the swelling.

Although chronic and bothersome, blepharitis can be controlled. Symptoms, however, are chronic, recurring, and remitting, and there may be no definitive cure. The problem can disappear for long periods of time and then return. Medication alone is not sufficient treatment, and keeping the eyelids clean is essential to restoring a normal, healthy environment.

What is a cataract?

The lens of the eye, the part that helps focus light onto the retina which in turn sends the visual signals to the brain (see Anatomy of the Eye), is made mostly of water and protein. When too much protein builds up, it clouds the lens blocking some of the light and impairing vision. That protein build-up is the formation of a cataract. It is not a growth, but rather a clouding or hazing of the lens.

How many people get cataracts?

A significant number of people ages 65 or older have some degree of cataract. In fact, developing cataracts is a normal part of aging. That does not mean, however, that every senior will need treatment for cataract problems.

What causes cataracts?

The cause of cataracts is generally unknown. Most often, cataracts occur as a person ages, called age-related cataracts or more scientifically, nuclear sclerotic cataracts. Cataracts can also result from a variety of environmental conditions and injuries and are called either secondary or traumatic cataracts. Some babies are born with cataracts, called congenital cataracts. Generally, potential risk factors for developing cataracts include but are not limited to:

- 65 years of age or more

- Family history of cataracts

- Smoker or former smoker

- Grossly over- or underweight

- Diabetes

- Have taken steroids or certain other medications

- Suffered a blunt or penetrating eye injury

- Excessive, long exposure to UV light

Some people compare cataracts to looking through a frosted piece of glass, fog, or film covering their sight. Many don’t even know they have cataracts if the cloudiness has not greatly altered their eyesight. Others with cataracts, however, have lost their ability to perform routine activities. Glare may also be a problem, and many people with cataracts complain of halos around lights.It is important to note, however, that although these symptoms can indicate the formation of cataracts, they can also signal other vision problems. Cataracts develop and grow slowly and cause more pronounced symptoms as they “mature.” Patients experiencing any of these symptoms are advised to consult their eye care professional for a thorough evaluation.

Some people compare cataracts to looking through a frosted piece of glass, fog, or film covering their sight. Many don’t even know they have cataracts if the cloudiness has not greatly altered their eyesight. Others with cataracts, however, have lost their ability to perform routine activities. Glare may also be a problem, and many people with cataracts complain of halos around lights.It is important to note, however, that although these symptoms can indicate the formation of cataracts, they can also signal other vision problems. Cataracts develop and grow slowly and cause more pronounced symptoms as they “mature.” Patients experiencing any of these symptoms are advised to consult their eye care professional for a thorough evaluation.

The first step in treating cataracts is detection. To determine whether or not a person has cataracts, an eye care professional conducts a comprehensive eye exam, which includes a visual acuity test, pupil dilation, and a tonometry test to measure the pressure inside the eye. The early stages of cataracts can sometimes be treated with eyeglasses, alternative lenses or a simple change in environmental lighting. For more advanced cataracts that have caused a loss of routine activities or other problems, surgery is the only effective treatment option. The entire lens is removed through a surgical incision and replaced with an intraocular lens (IOL). An IOL is a clear plastic lens implant that is placed inside the eye permanently, thus requiring no care. Patients do not feel or see the new lens.

What is involved in cataract surgery? The patient is given eye drops to enlarge the pupil of the eye to be operated on, giving the surgeon better access to the lens. Some people choose to remain awake during the procedure and select local anesthesia, which may be administered as eye drops, injections close to the eye, or both. Others require general anesthesia to keep them relaxed throughout the procedure.When ready, the patient lies back on a table and the eye is gently washed. Then a sheet is placed over the patient’s face with an opening for the surgeon to access the eye. Often, a member of the eye care team (surgeon, nurses, and assistants) provides additional air for increased comfort.

What happens after surgery? For a day or two following surgery, patients may experience mild discomfort such as itching or stickiness when blinking. These symptoms usually disappear within 1 to 2 days.The healing process may take weeks, but many patients begin to resume visual activities, such as reading and watching television, shortly after surgery, even with some blurred vision.As with any surgery, there are some risks involved in cataract surgery. A rise in the eye’s pressure is why it is essential for patients to follow a strict post-surgery check-up schedule. Because an incision is made in the eye, infection is also a risk, though managed easily with oral or eye-drop antibiotics. Other risks are hemorrhage or retinal detachment. It is important to point out that cataract surgery is common and risks are considered minimal. Patients are advised to discuss all the risks in detail with their eye care professional.

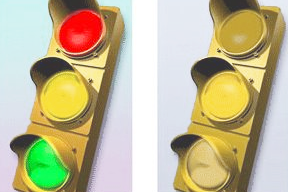

Color blindness is a condition in which a person has trouble telling the difference between various shades of color. Color blindness does not mean that a person sees things in black and white. Generally, optometrists and doctors refer to the condition as ‘color vision deficiency.

Who is affected by color vision deficiency?

Almost all color vision problems are inherited, and present at birth. It is estimated that 1 in every 12 males, and one in every 200 females, are born with some form of color vision deficiency.

In later life, some serious eye diseases, and certain medications can cause color vision deficiencies to appear.

How is a color vision deficiency inherited?

The ‘color blindness gene’ is passed down through the mother’s side of the family. A color blind male will have inherited the condition through his mother’s genes (although she will probably not be color blind). A color blind female will have inherited the condition through a combination of her mother’s genes (probably not color blind) and her father’s genes (color blind).

Who should be tested for color vision deficiency?

People who should have there color vision checked

- All Boys

- Girls in whom color vision is suspect

- Children with a family history of color blindness (particularly from uncles or grandfather)

- Adults considering occupations that require fine color discrimination

- Adults considering occupations that have color vision standards

- Adults who have developed eye disease, such as cataract or macula degeneration

Color vision testing is fairly simple, and can be carried out with little difficulty from the age of 3 years (the child doesn’t have to know the names of the colors).

What can be done about color blindness?

Medically, there is no cure for hereditary colorblindness, because the body lacks a given sensor for detecting particular colors. Color blind people often look for other cues to determine color. For example, if you couldn’t tell the difference between the red and the green at a traffic light, you could still tell that the top light meant stop! Other means of compensating for color blindness have been developed, such as specially tinted glasses. There are even computer programs available to help color blind people distinguish colors.

More commonly known as “pink eye”, conjunctivitis is an eye infection that can be highly contagious. It causes the conjunctiva, the thin transparent layer covering the inner eyelid and the white part of the eye, to become inflamed, irritated and red.

What causes conjunctivitis?

Conjunctivitis occurs most commonly in children, though it can occur at any age. There are generally four types of conjunctivitis:

viral — which accompanies a cold or other viral infection

viral — which accompanies a cold or other viral infection- bacterial — such as from strep, staph or other bacterial infections

- allergic — an allergy to dust, molds, pets, cosmetics and other potential irritants

- ophthalmia neonatorum — a form of conjunctivitis found only in newborns

Other possible causes of conjunctivitis include a partially blocked tear duct, unsanitary environments, and working with intense light.

Symptoms of conjunctivitis may be nothing more than a minor irritant to some people. Others, however, may notice several other, more painful, symptoms including itching, swelling, crusty eyelids after sleeping, a discharge from the eye, excessive watering, light sensitivity, and excessive redness.

How is it treated?

Most often, conjunctivitis disappears on its own with self-care and typically improves within one week. Because conjunctivitis spreads easily from eye to eye and person to person, it is important to exercise good hygiene during an episode of conjunctivitis. People with conjunctivitis should wash their hands frequently, avoid touching their eyes, refrain from wearing makeup, and not share towels, linens or other items in contact with the infected eye. To ease discomfort, warm-water compresses may be used, taking care to discard or launder the compress after use.

If symptoms do not resolve and the eye is left untreated, conjunctivitis can damage the cornea and affect vision permanently. Seek immediate medical attention if the conjunctivitis does not disappear or the following more severe symptoms occur:

- the symptoms begin to affect vision

- pain increases

- rapid recurrence

- discharge becomes greenish or yellowish

Usually, eye care professionals can test the discharge with a simple culture and establish the exact cause of conjunctivitis. In some cases, doctors may prescribe antiviral, antibiotic eye drops or ointments to control the infection. In cases of allergic conjunctivitis, removing the source of allergy may solve the problem, or antihistamine eye drops or steroid-based medications may be prescribed if removal of the allergen is not possible. Newborns are routinely treated with antibiotic eye drops or ointment.

The tough, clear membrane that covers the front of the eye and protects the inner parts of the eye is called the cornea. (See diagram under “Anatomy of the Eye.”) It serves as the outer lens of the eye and provides approximately 70 percent to 80 percent of the eye’s refractive power. Fine-tuning is provided by the natural crystalline lens that lies behind the pupil. Together these two lenses focus light on the retina at the back of the eye, which sends electrical signals to the brain enabling a person to see. The shape of the cornea and its general condition determine, to a large degree, the visual powers of the eye.

Although the cornea contains the highest concentration of nerve fibers of any structure in the human body, it contains no blood vessels. That is one reason why the cornea remains clear. The cornea receives nutrition from the fluid interior of the eye and from the outer tear film surface.

A corneal ulcer forms when the surface of the cornea is damaged. Ulcers may be sterile (no infecting organisms) or infectious. Whether or not an ulcer is infectious is an important distinction for the physician to make and determines the course of treatment. Bacterial ulcers tend to be extremely painful and are typically associated with a break in the epithelium, the superficial layer of the cornea. Certain types of bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, are extremely aggressive and can cause severe damage and even blindness within 24-48 hours if left untreated. Sterile infiltrates on the other hand, cause little if any pain. They are often found near the peripheral edge of the cornea and are not necessarily accompanied by a break in the epithelial layer of the cornea.

A corneal ulcer forms when the surface of the cornea is damaged. Ulcers may be sterile (no infecting organisms) or infectious. Whether or not an ulcer is infectious is an important distinction for the physician to make and determines the course of treatment. Bacterial ulcers tend to be extremely painful and are typically associated with a break in the epithelium, the superficial layer of the cornea. Certain types of bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, are extremely aggressive and can cause severe damage and even blindness within 24-48 hours if left untreated. Sterile infiltrates on the other hand, cause little if any pain. They are often found near the peripheral edge of the cornea and are not necessarily accompanied by a break in the epithelial layer of the cornea.

There are many causes of corneal ulcers. Contact lens wearers (especially soft) have an increased risk of ulcers if they do not adhere to strict regimens for the cleaning, handling, and disinfection of their lenses and cases. Soft contact lenses are designed to have very high water content and can easily absorb bacteria and infecting organisms if not cared for properly. Pseudomonas is a common cause of corneal ulcer seen in those who wear contacts.

Bacterial ulcers may be associated with diseases that compromise the corneal surface, creating a window of opportunity for organisms to infect the cornea. Patients with severely dry eyes, difficulty blinking, or are unable to care for themselves, are also at risk. Other causes of ulcers include: herpes simplex viral infections, inflammatory diseases, corneal abrasions or injuries, and other systemic diseases.

The symptoms associated with corneal ulcers depend on whether they are infectious or sterile, as well as the aggressiveness of the infecting organism.

- Red eye

- Severe pain (not in all cases)

- Tearing

- Discharge

- White spot on the cornea, that depending on the severity of the ulcer, may not be visible with the naked eye

- Light sensitivity

Corneal ulcers are diagnosed with a careful examination using a slit lamp microscope. Special types of eye drops containing dye such as fluorescein may be instilled to highlight the ulcer, making it easier to detect. If an infectious organism is suspected, the doctor may order a culture. After numbing the eye with topical eye drops, cells are gently scraped from the corneal surface and tested to determine the infecting organism.

The course of treatment depends on whether the ulcer is sterile or infectious. Bacterial ulcers require aggressive treatment. In some cases, antibacterial eye drops are used every 15 minutes. Steroid medications are avoided in cases of infectious ulcers. Some patients with severe ulcers may require hospitalization for IV antibiotics and around-the-clock therapy. Sterile ulcers are typically treated by reducing the eye’s inflammatory response with steroid drops, anti-inflammatory drops, and antibiotics.

Dry eye is a term used to describe a condition in which the eyes either produce too few tears or they tear without the proper chemical composition. There may be as many as 34 million Americans who experience some of the symptoms of dry eye. The condition is most often the result of the natural aging process. However, it may also be caused by:

Dry eye is a term used to describe a condition in which the eyes either produce too few tears or they tear without the proper chemical composition. There may be as many as 34 million Americans who experience some of the symptoms of dry eye. The condition is most often the result of the natural aging process. However, it may also be caused by:

- Problems with the blinking reflex

- The use of certain types of medications

- Environmental factors such as a dry climate or exposure to wind

- Chemical or thermal burns to the eye

- Some health problems, such as arthritis or Sjogren’s syndrome.

One of the symptoms of dry eye is excessive watering of the affected eye. The watering is a natural reflex, caused by irritation of the surface of the eye because the tears are of abnormal chemical composition. This symptom is one of the primary reasons why so many people with the disorder do not consider the possibility that the term “dry eye” might apply to them. Other symptoms are an eye that is scratchy, dry, irritated or generally uncomfortable. Sometimes redness, a burning sensation, or the feeling of having something in your eye may also occur.

Because these symptoms can occur in conjunction with many disorders, the only way to be sure about a condition with such symptoms is to visit an eye doctor.

Esotropia is the most common form of strabismus, a condition that refers to any misalignment of the eyes. In the case of esotropia, one eye deviates inward toward the nose while the other fixates normally. (Exotropia is the condition where one eye deviates outward, away from the nose.) Strabismus, also called “cross-eye,” occurs in about four percent of all children in the United States. It happens equally in males and females and is sometimes hereditary. Esotropia can also affect teenagers and adults, and it is usually related to systemic conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, strokes, or brain injuries.

Esotropia is the most common form of strabismus, a condition that refers to any misalignment of the eyes. In the case of esotropia, one eye deviates inward toward the nose while the other fixates normally. (Exotropia is the condition where one eye deviates outward, away from the nose.) Strabismus, also called “cross-eye,” occurs in about four percent of all children in the United States. It happens equally in males and females and is sometimes hereditary. Esotropia can also affect teenagers and adults, and it is usually related to systemic conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, strokes, or brain injuries.

The brain’s ability to see three-dimensional objects depends on proper alignment of the eyes. When both eyes are properly aligned and aimed at the same target, the visual portion of the brain fuses the forms into a single image. When one eye turns inward, outward, upward, or downward, two different pictures are sent to the brain. This causes loss of depth perception and binocular vision, or use of the two eyes together.

Types of Esotopia

- Pseudoesotropia (false esotropia) is actually the physical appearance of cross-eye when the eyes are perfectly aligned. Infants and young children often have a wide, flat nose with a fold of skin at the inner eyelid that makes the eyes appear crossed. This appearance usually disappears as the child grows.

- Congenital or infant esotropia can be present at birth or may develop anytime during the first 6 months of life. Although it is common for an infant’s eyes to be intermittently misaligned, if the condition persists beyond the first few months, it should be checked by a physician. One to 2 percent of children have congenital esotropia, and the condition usually does not improve with age. Surgical correction is usually recommended between 6 and 14 months of age.

- Accommodative esotropia is a common form that occurs in farsighted children, usually 2 years old or older. Young children can often overcome farsightedness by focusing their eyes to adjust to the condition, but the effort required for this focusing causes the eyes to cross. Eyeglasses can reduce the focusing effort and sometimes straighten the eyes. In addition, special eyedrops, ointments, and lenses called prisms may also be effective. Eye exercises can also be helpful, especially in older children. Sometimes bifocals can correct the excessive turning in of the eyes for close work.

- Acquired esotropia occurs after infancy. Children who have been farsighted and have not had glasses, or children who were responsive to glasses but later developed an additional eye-crossing, are the most commonly affected. Children with acquired eye-crossing require prompt evaluation and treatment to correct the deviation and to restore binocular vision.

The causes of some forms of esotropia are not fully understood. There are six muscles that control eye movement, four that move it up and down and two that move it side to side. All these muscles must be coordinated and working properly in order for the brain to see a single image. When one or more of these muscles doesn’t work properly, some form of strabismus may occur. Strabismus is more common in children with disorders that affect the brain such as cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, hydrocephalus, and brain tumors.

What are the symptoms of esotropia?

Symptoms of esotropia are decreased vision, double vision, and misaligned eyes. Children with esotropia do not use their eyes together and often squint in bright sunlight or tilt their heads in a specific direction to use their eyes together. They may also rub their eyes frequently. Children rarely tell you they are experiencing double vision, although they may close one eye to compensate for the problem. You may also notice signs of faulty depth perception.

When a young child has strabismus, the child’s brain may learn to ignore the misaligned eye’s image and see only the image from the best-seeing eye. This is called amblyopia, or lazy eye, and results in a loss of depth perception. In adults who develop strabismus, double vision sometimes occurs because the brain has already been trained to receive images from both eyes and cannot ignore the image from the turned eye.

What are the cures for esotropia?

Treatment depends on the type of esotropia. Generally, however, treatment can include correcting a refractive error with glasses, patching to force the use of the less-preferred eye, and vision therapy to train the eyes to work together. Sometimes surgery is required.

Exotropia is one of the most common forms of strabismus, a condition that refers to any misalignment of the eyes. In the case of exotropia, one eye deviates outward (away from the nose) while the other fixates normally. Esotropia is the condition where one eye deviates inward (toward the nose). Esotropia is the most common type of strabismus in infants, while exotropia often begins between the ages of 2 and 4. About 4 percent of all children in the United States have some form of strabismus. It occurs equally in males and females and is sometimes hereditary. The condition can also develop later in life.

Exotropia is one of the most common forms of strabismus, a condition that refers to any misalignment of the eyes. In the case of exotropia, one eye deviates outward (away from the nose) while the other fixates normally. Esotropia is the condition where one eye deviates inward (toward the nose). Esotropia is the most common type of strabismus in infants, while exotropia often begins between the ages of 2 and 4. About 4 percent of all children in the United States have some form of strabismus. It occurs equally in males and females and is sometimes hereditary. The condition can also develop later in life.

The brain’s ability to see three-dimensional objects depends on proper alignment of the eyes. When both eyes are properly aligned and aimed at the same target, the visual portion of the brain fuses the forms into a single image. When one eye turns inward, outward, upward, or downward, two different pictures are sent to the brain. This causes loss of depth perception and binocularity, or normal two-eyed vision.

How does exotropia occur?

The causes of exotropia are not fully understood. There are six muscles that control eye movement, four that move it up and down and two that move it side to side. All these muscles must be coordinated and working properly in order for the brain to see a single image. When one or more of these muscles doesn’t work properly, some form of strabismus may occur. Strabismus is more common in children with disorders that affect the brain such as cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, hydrocephalus, and brain tumors.

What are the signs of exotropia?

The earliest sign of exotropia is usually a noticeable outward deviation of the eye. This symptom may at first be intermittent, occurring when a child is daydreaming, not feeling well, or tired. The deviation may also be more noticeable when the child looks at something in the distance. Squinting or frequent rubbing of the eyes is also common with exotropia. Your child probably will not mention seeing double, i.e., double vision. However, he or she may close one eye to compensate for the problem.

Generally, exotropia progresses in frequency and duration. As the disorder progresses, the eyes will start to turn out when looking at close objects as well as those in the distance. If left untreated, the eye may turn out continually, causing a loss of binocular vision.

In young children with any form of strabismus, the brain may learn to ignore the misaligned eye’s image and see only the image from the best-seeing eye. This is called amblyopia, or lazy eye, and results in a loss of depth perception. In adults who develop strabismus, double vision sometimes occurs because the brain has already been trained to receive images from both eyes and cannot ignore the image from the turned eye.

How is exotropia treated?

A comprehensive eye examination including an ocular motility (eye movement) evaluation and an evaluation of the internal ocular structures will allow an eye doctor to accurately diagnose the exotropia. Exotropia responds very well to vision therapy to train the eyes to work together. Eye patching is usually required and prisms are occasionally used. In some children, surgery is required.

Farsightedness is an inherited condition that occurs when the cornea is too flat or the distance from the cornea to the retina is too short. When this happens, the light rays coming from an object strike the retina before coming to sharp focus, or the image is theoretically focused at an imaginary point behind the retina. The result is a blurred image when trying to focus on something that is up close, but distance vision remains sharp.

Children who are farsighted can sometimes compensate without corrective lenses because of the strength and agility of their natural lenses. With a high degree of hyperopia, however, they may exhibit nonvisual symptoms such as headaches and lack of interest in reading. As the eye gets older, it loses some of its ability to accommodate (focus), and eventually, most farsighted individuals need corrective lenses.

How is farsightedness corrected?

The usual treatment for hyperopia is prescription eyeglasses with convex lenses that curve outward, or contact lenses that counteract the distortion created by corneas that are too flat in shape. A convex lens moves the image of a distant object forward onto the retina, thereby bringing it into proper focus.

Floaters are small grayish or transparent spots or blobs that float across the field of vision from time to time. Floaters move around with eye movements, and are most commonly noticed against plain backgrounds, such as a white page or a blank wall. Floaters can also appear as fine threads, webs, and clumps. Floaters are caused by small specks or clumps that form within the fluid of the eye. When light enters the eye, these clumps cast a shadow onto the retina. The floater that you notice is the shadow that is cast onto the retina. Floaters are an annoying phenomenon that get in the way. Mostly they are harmless. In a small number of cases, floaters can be a sign of more serious damage that is taking place. Floaters can occur in anyone, at any time.

What should I do if I think I might have floaters?

You should arrange for an eye examination with your local optometrist to rule out more serious underlying problems. You should seek immediate attention if you notice any of the following symptoms:

- An increase in the number of floaters noticed

- Decrease in vision in one or both eyes

- Flashes or sparkles in vision

Your optometrist will advise you if you have floaters, and whether or not they are potentially dangerous to your vision. Generally, floaters are annoying. But no treatment is required (provided there are no underlying problems).

Glaucoma is a very evasive and dangerous eye disease. It can happen to people without their knowledge and can cause partial, sometimes, total blindness. In fact, glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in the United States.

In simple terms, glaucoma is caused by the excessive buildup of fluid inside the eye. Eyes are essentially hollow globes filled with a constantly circulating clear fluid that must drain out of the eye as more is pumped in. Each eye produces about 4 c.c. of fluid a day, a considerable amount for an object that is only about 1 inch in diameter.

Sometimes the eye’s drainage system becomes clogged, causing pressure in the eye to build up to damaging levels. Unless controlled, damage to the optic nerve and loss of vision can occur. The earliest sign of optic nerve damage is often a loss of peripheral (side) vision. However, the early onset of glaucoma can be detected not by any symptoms but by a comprehensive eye exam and specific glaucoma tests.

How many are affected by glaucoma?

The most common form of glaucoma is called open-angle glaucoma. It is so named because the angle from which the fluid drains out of the anterior chamber is open. This form of glaucoma affects approximately 3 million Americans. Glaucoma occurs in nearly 1 to 2 percent of people over the age of 40.

What causes glaucoma?

There is no single cause of glaucoma. Anyone can develop glaucoma, but generally, those at higher risk than the average population are:

- People more than 60 years of age

- African Americans over the age of 40

- People with a family history of glaucoma

What are the symptoms of glaucoma?

What are the symptoms of glaucoma?

Only an eye care professional can determine whether or not a person has glaucoma and how severe it is. Glaucoma begins without showing any symptoms. If it remains untreated and undetected, a person may notice a loss of peripheral vision and the start of tunnel vision. Gradually, sight diminishes completely. A few glaucoma sufferers have such early symptoms as severe eye pain, blurred vision, seeing halos around lights, and constantly dilated pupils, though these are the exceptions.

Note that experiencing these symptoms does not necessarily signal glaucoma. Patients with any changes in their vision or optical comfort should see an eye care professional for a thorough evaluation.

How is glaucoma detected?

Detection is vital. For patients, understanding glaucoma helps in both treatment and long-term eye care. Pressure is key. Glaucoma can occur in eyes with “normal” pressure readings, though “normal” pressure varies from person to person. The pressure’s effect on, or the potential risk to, the optic nerve determines the severity of glaucoma.

To determine whether a person has glaucoma, an eye care professional conducts several tests. A tonometry test measures the amount of pressure on the optic nerve and is usually part of every complete eye exam.

A popular tonometry test is often referred to as the “air-puff” test. The patient looks through a machine as it blows a puff of air at the eye.

Another form of tonometry, and one of the most accurate, uses a contact tonometer, an instrument that looks like a pen. After numbing eye drops are administered, the tip of the tonometer touches the eye and measures the pressure.

As a general guideline, pressure above 21 millimeters is considered to be elevated, though not all persons with that reading will have glaucoma. Eye care professionals will carefully monitor pressures for early signs of glaucoma.

Another test used in detection is an examination of the optic nerve, looking at the interior of the eye to detect any damage. A pupil dilation test provides the eye care professional to get a better look at the inner eye. A visual acuity test helps to evaluate peripheral vision.

What are the treatments for glaucoma?

Medication: The first line of treatment is often the use of eye drops administered three times per day or oral medication to help drain the fluid and lower pressure. Sometimes eye drops or pills are enough to lower pressure. As with all medications, it is important to give the eye care professional a complete history of current medications, allergies or any other side effects experienced from the medication. Following the eye drops and oral medication directions closely is equally important.

Laser Surgery: When pressure cannot be lowered adequately or side effects are too severe, eye care professionals turn to laser treatment as the next, and necessary, treatment. Laser surgery uses focused light to reopen the drainage area to alleviate the buildup of fluid. After receiving a numbing agent in the eyes, patients sit facing the laser machine, while the eye care professional gently holds a lens used to aim the laser beam to the eye. A beam of light hits the eye’s lens and reflects into the drainage area of the eye. The entire procedure usually takes only minutes.

Generally, there are no restrictions following laser surgery, but patients are given eye medications to use for a few days after the procedure. Eye care professionals will continue to monitor pressure closely and regularly. Some consider laser surgery a temporary method to reducing pressure. Studies indicate that the effects of laser surgery diminish over time. More than half of all patients undergoing laser surgery show pressure increases in just two years after surgery.

Conventional surgery: Conventional surgery for glaucoma involves making an incision in the eye to create a new drainage path. The eye tissue creates a new area for fluid to drain naturally. Patients cannot feel this draining. The procedure takes about 10 to 15 minutes. Eye medication is used to prevent infection. This surgery typically requires close follow-up and a lot of care afterward. Studies on the effect of surgery indicate that 80 percent to 90 percent of patients have lowered pressure readings after the surgery. However, there is no cure for glaucoma. Surgery may save remaining vision but it cannot improve sight that has already been impaired or lost.

What are the forms of glaucoma?

There are many types of glaucoma. Open-angle glaucoma is the most common. All are similar because they relate to an increase or a buildup of pressure inside the eye.

Angle-closure or closed-angle glaucoma is characterized by intense pain, starting with a headache and including such other symptoms as nausea, red eye, and blurred vision. Angle-closure glaucoma can occur all at once and be severe, or gradually in small episodes. Both of these types require immediate medical attention.

Secondary glaucoma occurs as a result of some other medical problem with the eye, such as inflammation, injury, advanced cataracts, or certain tumors. Congenital glaucoma occurs in children born with malformations in the angle of the eye. Usually, parents detect symptoms, such as eyes that appear cloudy, severe sensitivity to light, and excessive tearing or watery eyes. Many eye care professionals recommend surgery over eye drops, because of the difficulty of administering drops in infants and the unknown effects of the drops on young eyes. Surgery on children usually results in adequate vision.

Because of the many unknown factors surrounding glaucoma, research is focusing on ways to service patients with the disease. Patients with questions or concerns regarding glaucoma should contact their eye care professional or a professional organization dedicated to glaucoma research.

Herpes simplex is a very common virus affecting the skin, mucous membranes, nervous system, and the eye. There are two types of herpes simplex. Type I causes cold sores or fever blisters and may involve the eye. Type II is sexually transmitted and rarely causes ocular problems.

Nearly everyone is exposed to the virus during childhood. Herpes simplex is transmitted through bodily fluids, and children are often infected by the saliva of an adult. The initial infection is usually mild, causing only a sore throat or mouth. After exposure, herpes simplex usually lies dormant in the nerve that supplies the eye and skin.

Later on, the virus may be reactivated by stress, heat, running a fever, sunlight, hormonal changes, trauma, or certain medications. It is more likely to recur in people who have diseases that suppress their immune system. In some cases, the recurrence is triggered repeatedly and becomes a chronic problem.

When the eye is involved, herpes simplex typically affects the eyelids, conjunctiva, and cornea. Keratitis (swelling caused by the infection), a problem affecting the cornea, is often the first ocular sign of the disease. In some cases, the infection extends to the middle layers of the cornea, increasing the possibility of permanent scarring. Some patients develop uveitis, an inflammatory condition that affects other eye tissues.

Signs and Symptoms

- Pain

- Red eye

- Tearing

- Light sensitivity

- Irritation, scratchiness

- Decreased vision (dependent on the location and extent of the infection)

Herpes simplex is diagnosed with a slit lamp examination. Tinted eye drops that highlight the affected areas of the cornea may be instilled to help the doctor evaluate the extent of the infection. Treatment of herpes simplex keratitis depends on the severity. An initial outbreak is typically treated with topical and sometimes oral anti-viral medication. The doctor may gently scrape the affected area of the cornea to remove the diseased cells. Patients who experience permanent corneal scarring as a result of severe and recurrent infections may require a corneal transplant to restore their vision.

Keratoconus is a degenerative disease of the cornea that causes it to gradually thin and bulge into a cone-like shape. This shape prevents light from focusing precisely on the macula. As the disease progresses, the cone becomes more pronounced, causing vision to become blurred and distorted. Because of the cornea’s irregular shape, patients with keratoconus are usually very nearsighted and have a high degree of astigmatism that is not correctable with glasses.

Keratoconus is a degenerative disease of the cornea that causes it to gradually thin and bulge into a cone-like shape. This shape prevents light from focusing precisely on the macula. As the disease progresses, the cone becomes more pronounced, causing vision to become blurred and distorted. Because of the cornea’s irregular shape, patients with keratoconus are usually very nearsighted and have a high degree of astigmatism that is not correctable with glasses.

Keratoconus is sometimes an inherited problem that usually occurs in both eyes.

Signs and Symptoms

- Nearsightedness

- Astigmatism

- Blurred vision – even when wearing glasses and contact lenses

- Glare at night

- Light sensitivity

- Frequent prescription changes in glasses and contact lenses

- Eye rubbing

Keratoconus is usually diagnosed when patients reach their 20′s. For some, it may advance over several decades, for others, the progression may reach a certain point and stop. Keratoconus is not usually visible to the naked eye until the later stages of the disease. In severe cases, the cone shape is visible to an observer when the patient looks down while the upper lid is lifted. When looking down, the lower lid is no longer shaped like an arc, but bows outward around the pointed cornea. This is called Munson’s sign.

Special corneal testing called topography provides the doctor with detail about the cornea’s shape and is used to detect and monitor the progression of the disease. A pachymeter may also be used to measure the thickness of the cornea. The first line of treatment for patients with keratoconus is to fit rigid gas permeable (RGP) contact lenses. Because this type of contact is not flexible, it creates a smooth, evenly shaped surface to see through. However, because of the cornea’s irregular shape, these lenses can be very challenging to fit. This process often requires a great deal of time and patience. When vision deteriorates to the point that contact lenses no longer provide satisfactory vision, corneal transplant may be necessary to replace the diseased cornea with a healthy one.

LASIK is now the most popular of all laser vision correction procedures. The first step in the LASIK procedure is the creation of a flap of tissue from the outer layer of the central zone of the cornea using the microkeratome. The flap is then folded back out of the way, but it is held ready for replacement upon completion of the procedure. The excimer laser is then used to sculpt the remaining central zone in accordance with pre-determined data that has been entered into the laser system’s computer. Under this precise control, the laser reshapes the curvature of the cornea to correct for nearsightedness, farsightedness, or astigmatism. This part of the procedure takes only 30 to 60 seconds, after which the corneal flap is replaced. No sutures are used, and the surface of the eye will normally heal itself. Most patients can see quite well within 24 hours or less. Complete healing of the cornea takes about one month.

The LASIK procedure is performed on an outpatient basis. Although the actual laser procedure takes only a few seconds per eye, the procedure requires a couple of hours at the surgery center. Some of this time is spent preparing the patient for the procedure, while a few minutes are required afterwards for post-operative instructions and departure preparation.

How is the procedure performed?

Step 1: Eye preparation Before the procedure begins, a nurse or technician talks to the patient about any immediate health problems that may affect readiness for the procedure. Antibiotic and anesthetic eye drops are then placed in the eye to numb it and prevent infection. The eye is swabbed with a sterile solution. The eyelid is then propped open with a lid retainer, and a paper or plastic “mask” is placed over the eye to keep eyelashes out of the way. Then the cornea is marked with a blue “dye ring,” which serves as a reference point for the surgeon throughout the procedure. Because the cornea is numb, most patients experience little if any discomfort during these pre-operative preparations.

Step 2: Creating the flap Next, the doctor creates a flap from the central zone of the cornea using the microkeratome. This precision instrument works much like a miniature carpenter’s plane. It contains a disposable cutting blade that is preset according to the thickness of the cornea — usually about 160 to 180 microns or 1/3 the depth of the cornea. The microkeratome operates in conjunction with a suction ring that holds the eye perfectly still, and when activated by a vacuum tube, it raises and flattens the cornea so it can be reached easily for cutting the flap.

Step 3: The Excimer laser After the flap has been folded back from the center of the eye, the doctor dries the underlying cornea with a sponge-tipped swab and aligns the Excimer laser’s microscope with the central corneal area in order to monitor the laser’s sculpting pulsations. The patient is asked to focus on a fuzzy red light inside the laser. As the doctor activates the laser, there is a “popping” or “tacking” sound, and there is a slight odor similar to that of hair burning, but no discomfort for the patient. The number of laser pulsations will depend on the nature of the refractive vision problem that is being corrected. This phase of the procedure takes only a minute or so. The doctor then carefully folds the flap back in place and irrigates the eye with a sterile saline solution. The corneal area may be dried with a gentle blower, which helps seal the flap. In addition, a contact lens may be placed in the eye.

Step 4: Post-operative measures When the procedure is complete, additional antibiotic drops are placed in the eye, and it may be covered with a plastic shield. For a short while after the procedure, the eye is numb from the anesthetic drops. As the numbness wears off, the patient may experience some light sensitivity and a scratchy or dry sensation as though something is in the eye. This feeling usually goes away within a few hours. Patients must not drive themselves home following the procedure.

The patient returns to the doctor’s office the next day for a post-operative examination. The doctor checks the flap to see if it is healing properly. If a contact lens was placed after surgery, it will be removed at this time. Vision is checked and, for most patients will range from 20/20 to 20/40 depending on the number of laser pulsations received. For some patients, vision may continue to improve for several weeks before totally stabilizing.

The macula is a small area — less than ¼ inch — in the center of the retina at the back of the eye (See Anatomy of the Eye). It is responsible for sharp, clear central vision and the ability to perceive color.

How does the macula function?

Like the film in a camera, the retina receives light rays from the front of the eye and transmits those light rays through the optic nerve to the brain where the rays are converted into images. The densely packed photoreceptor (light-sensitive) cells in the macula control all of the eye’s central vision and are responsible for the ability to read, drive a car, watch television, see faces, and distinguish detail. The rest of the retina handles peripheral vision that enables your eyes to see objects off to the side while you are looking forward.

There are two types of photoreceptor cells in the retina — rods and cones. The rods provide vision at low light levels, while the cones provide sharp vision and discrimination. Because the macula contains a high concentration of cones, straight-ahead vision is in sharp focus, particularly in bright light. Most of the rods are located in the periphery of the retina, so faint objects are more visible if you do not look directly at them. A dim star, for instance, is best seen when your eyes are not aimed directly at it.

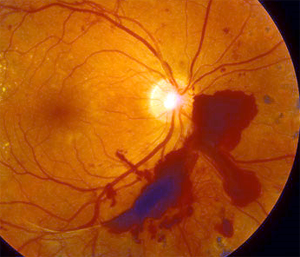

Age-related macular degeneration is a progressive disorder of the tiny central part of the retina, called the macula (see Anatomy of the Eye), that gradually destroys central vision, making reading or driving difficult or impossible. Although some peripheral vision remains, a person with macular degeneration has increasing difficulty in reading, watching television, or even recognizing friends.

Because it is an age-related disease, the incidence of macular degeneration is growing as the mature population increases. An estimated 400,000 Americans develop a serious form of the disease every year.

What causes Macular Degeneration? What are the risk factors?

Although the macula occupies only 2 percent of the retina, it contains about 25 percent of the light-sensing cone cells, which are specialized for daylight vision. macular degeneration occurs when this central part of the retina and the layer of cells underneath it, which is the retinal pigment epithelium, begin to deteriorate, for reasons that are not clear. Genetics may play a role in some cases, because the disease can run in families.

There are two forms of macular degeneration, dry and wet. The “dry” form, which accounts for 85 percent to 90 percent of all cases, does not cause blindness but does cause a loss of central vision that can produce grayness, haziness, or a blind spot in the central area of vision. In the dry form of the disease, tiny white deposits called drusen accumulate in the retina, and there is a thinning of macular tissue. The cause is unknown, although lifetime exposure to sunlight and smoking may increase the risk. In “wet” macular degeneration cases, which account for 10 percent to 15 percent of all cases, abnormal blood vessels grow under the retina, scarring or destroying retinal tissue and often causing sudden blindness. The wet form causes most macular degeneration-related blindness.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of macular degeneration are blurred vision, loss of color perception, a dark or empty spot in the center of the field of vision, and seeing crooked lines that are really straight. The condition can be diagnosed in several ways: with an ophthalmoscope, a slit lamp lens, an Amsler Grid test, photographing the back of the eye, fluorescein angiography, and/or macular pigment density testing. People over the age of 65 are advised to see an ophthalmologist once a year for a complete eye examination, and any sudden change in vision should be reported to an ophthalmologist. If dry macular degeneration is detected, close follow-up is recommended to monitor for indications of the wet form.

The symptoms of macular degeneration are blurred vision, loss of color perception, a dark or empty spot in the center of the field of vision, and seeing crooked lines that are really straight. The condition can be diagnosed in several ways: with an ophthalmoscope, a slit lamp lens, an Amsler Grid test, photographing the back of the eye, fluorescein angiography, and/or macular pigment density testing. People over the age of 65 are advised to see an ophthalmologist once a year for a complete eye examination, and any sudden change in vision should be reported to an ophthalmologist. If dry macular degeneration is detected, close follow-up is recommended to monitor for indications of the wet form.

What treatments are recommended for macular degeneration?

Several techniques are used to treat wet macular degeneration:

- Laser photocoagulation surgery uses a powerful beam of light to attack the abnormal blood vessels. Early diagnosis is important because this treatment is effective only in the early stages of the disease. The surgery often does not stop the progression of abnormal blood vessels, so repeat treatments are needed. The surgery can destroy some healthy tissue, causing some loss of vision.

- Still somewhat experimental, photodynamic therapy uses verteporfin (brand name Visudyne), a photosensitive dye that goes to the abnormal blood vessels. Light from a low-powered laser triggers a chemical reaction that destroys the blood vessels. Photodynamic therapy generates less heat than photocoagulation, and thus causes less damage to healthy tissue.

- Another treatment involves surgery to detach the retina and rotate it, so that the macula is no longer in the region of abnormal blood vessel growth.

- Surgery can also be used to remove the abnormal blood vessels.

- Thalidomide, notorious for causing birth defects, is being tried as a treatment because it blocks blood vessel development.

What can be done to decrease the likelihood of developing macular degeneration?

There is evidence that chemicals called antioxidants, which include vitamins C and E, can protect the macula. So can carotenoids, which include beta-carotene, and the mineral selenium. Field trials to determine whether vitamin therapy can be effective against macular degeneration have begun. The National Institutes of Health has started a study to determine whether estrogen replacement after the menopause can prevent or slow the progression of macular degeneration.

Nearsightedness, or myopia, is the ability of the eye to clearly see objects that are up close, but not far away. A nearsighted person can usually see well to read, but has trouble with distance vision, such as that used in driving. This is a common refractive eye condition created when the eyeball is more elongated than normal from front to back, or the cornea is too steep or dome-shaped. Myopia is an inherited condition that affects about one person in five.

In a myopic eye, the light rays are passed through the cornea and lens but the point at which they converge (focus) is in front of the retina, not on the retina. This configuration allows clear images of near objects but not those that are far away. Non- surgical treatment options for myopia include glasses and contact lenses. Surgical treatment options include clear lens extraction or LASIK surgery. While there are numerous surgical options available, not all individuals are good candidates for specific procedures. Patients should review these options in depth with their eye doctor prior to making any final decisions.

How is nearsightedness corrected?

The usual treatment for nearsightedness is prescription eyeglasses with concave (inwardly curved) lenses or contact lenses that counteract the distortion created by corneas that are too outwardly curved in shape. A concave lens moves the image of a distant object backward onto the retina, thereby bringing it into proper focus.

Refractive eye surgery, which flattens the cornea, has also become a popular option for the correction of nearsightedness in recent years. The most popular of those procedures is LASIK, (Laser in-Situ Keratomileusis0 which uses an Excimer laser to reshape the cornea, often eliminating the need for corrective lenses. Another option that is becoming popular is Intrastromal Corneal Ring Segments (ICRSs), tiny plastic arcs that are implanted in the peripheral area of the cornea, causing the center of the cornea to flatten. These segments can be removed and/or replaced if needed. Refractive eye surgery is usually not recommended for people under 18 years of age.

Ocular hypertension occurs when the intraocular pressure in your eyes is above the normal range, but it has not yet affected your vision or damaged the structure of your eyes. Normal eye pressure usually ranges between 10 and 21 mm of mercury. Pressure consistently above 21 indicates ocular hypertension. The condition can develop into glaucoma, a serious disease that causes damage to the optic nerve.

Who is at risk for ocular hypertension?

Most at risk for developing ocular hypertension are African Americans and those with a family history of the condition. It is also more common in those who are nearsighted, have high blood pressure, or are diabetic. Because ocular hypertension has no outward symptoms, people over the age of 40 and those in a high-risk category for glaucoma should have their pressure checked every year. A pressure check is a painless procedure that is part of any comprehensive eye examination.

What causes ocular hypertension?

In simple terms, ocular hypertension is caused by an excessive buildup of fluid inside the eye. This fluid, or aqueous humor, nourishes the cornea, iris, and lens, and maintains intraocular pressure. The typical eye produces about 4 c.c. of fluid a day, which circulates and then drains out of the eye If the drainage system becomes clogged or if too much fluid is produced, pressure inside the eye can build up. The reasons for this are not fully understood.

There are normally no symptoms of ocular hypertension, which is one of the reasons why regular eye examinations are so important. Although ocular hypertension in itself is not sight threatening, if pressure within the eye builds to the point where it damages the optic nerve (glaucoma), eyesight can be permanently damaged.

How is ocular hypertension checked?

An instrument called a tonometer is used to check eye pressure. There are two types of tonometers. One is called an applanation tonometer and uses an instrument that looks somewhat like a pen. After numbing eyedrops are administered, the instrument is applied gently to the front surface of the eye and provides a pressure reading. The other type is a noncontact tonometer, which directs a warm puff of air toward the eye without touching it.

Neither ocular hypertension nor glaucoma can be prevented or cured, and ocular hypertension does not usually require treatment unless it progresses to glaucoma. Some doctors may, however, treat the condition with eye drops or other medicines as a precautionary measure. After you are diagnosed with ocular hypertension, your eye health must be monitored closely.

Orthokeratology is a non-surgical procedure where you wear special contact lenses that slowly reshape the surface of the eye (cornea) to correct your myopia, or nearsightedness. When the lenses are removed, the cornea temporarily retains its new shape so you can see clearly without glasses or contacts. Orthokeratology uses special rigid gas permeable contact lenses. You wear these lenses at night. As you sleep, the lenses gently reshape the surface of the eye so that you can see clearly when you remove them. The effect is temporary; the lenses must be worn each night to ensure clear vision without glasses or contacts during the day.

Presbyopia, also known as the “short arm syndrome,” is a term used to describe an eye in which the natural lens can no longer accommodate. Accommodation is the eye’s way of changing its focusing distance: the lens thickens, increasing its ability to focus close-up. At about the age of 40, the lens becomes less flexible and accommodation is gradually lost. It’s a normal process that everyone eventually experiences.

Presbyopia, also known as the “short arm syndrome,” is a term used to describe an eye in which the natural lens can no longer accommodate. Accommodation is the eye’s way of changing its focusing distance: the lens thickens, increasing its ability to focus close-up. At about the age of 40, the lens becomes less flexible and accommodation is gradually lost. It’s a normal process that everyone eventually experiences.

Most people first notice difficulty reading very fine print such as the phone book, a medicine bottle, or the stock market page. Print seems to have less contrast and the eyes become easily fatigued when reading a book or computer screen. Early on, holding reading material further away helps for many patients. But eventually, reading correction in the form of reading glasses, bifocals, or contact lenses is needed for close work. However, nearsighted people can simply take their glasses off because they see best close-up.

Signs and Symptoms

- Difficulty seeing clearly for close work

- Print seems to have less contrast

- Brighter, more direct light required for reading

- Reading material must be held further away to see (for some)

- Fatigue and eyestrain when reading

Presbyopia is detected with vision testing and a refraction. The treatment for presbyopia is very simple, but is entirely dependent on the individual’s age, lifestyle, occupation, and hobbies. If the patient has good distance vision and only has difficulty seeing up close, reading glasses are usually the easiest solution. For others, bifocals (glasses with reading and distance correction) or separate pairs of reading and distance glasses are necessary. Another option is monovision: adjusting one eye for distance vision, and the fellow eye for reading vision. This can be done with contact lenses or permanently with refractive surgery.

The retina is the light-sensitive membrane that covers the inside of the back of the eye. It receives the images that come through the cornea and lens. The retina contains light-sensitive nerve cells, the rods and cones, which send nerve impulses along the optic nerve to the brain by way of a network of connecting and integrating cells, some of which have very long fibers.

The rods and cones are specialized for different purposes. The rods perceive light, while the cone cells perceive both light and color. The retina has 20 times more rod cells than cone cells. Because there are fewer cone cells and because they need more light to function, it is difficult to discern colors in dim light.

At the center of the retina is an area called the fovea, which has no blood vessels. Light-sensitive cells, primarily cones, are packed tightly in the fovea, so that it has the highest visual resolution.

How is the retina examined?

When conducting an eye examination, the examiner uses the ophthalmoscope, a hand-held device with a bright light, to examine the retina. The eye care professional looks for such abnormal conditions as damage to the tiny blood vessels that can be caused by high blood pressure or diabetes, detachment of the retina from the back of the eyeball, or blank spots on surface of the eyeball.

What causes retinal damage?

Heavy drinking and cigarette smoking, along with poor nutrition, can also lead to retinal damage, as can vitamin deficiency and lead poisoning.

What are some other retinal diseases and disorders?

Retinitis pigmentosa This is a gradual degeneration of the rods and cones that can begin as early as adolescence but most commonly occurs in middle age.

Tay-Sachs disease Tay-Sachs affects not only the eye but also the brain, causing early death.

Age-related macular degeneration An age-related retinal disorder is macular degeneration, gradual deterioration of the innermost part of the retina, the macula. There are two kinds of macular generation, wet and dry. In both kinds, there is a gradual breakdown of cells of the macula and the layer of cells below it, the retinal pigment epithelium.

The “dry” form is most common, accounting for about 90 percent of cases. Progressive breakdown of the cells causes a blind spot in the center of the eye. The “wet” form is caused by an overgrowth of blood cells in the area of the macula. Wet macular degeneration can be treated to some extent, but the dry form is currently untreatable.

Retinopathy Retinopathy is a term used to describe a variety of disorders of the retina.

Retinopathy Retinopathy is a term used to describe a variety of disorders of the retina.

One form is diabetic retinopathy, damage to the retina and the blood vessels that serve it when diabetes is not well controlled. The blood vessels can leak or burst, new vessels can grow on the surface of the retina, and there can be abnormal growth of fibrous tissue. Diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of loss of vision.

Hypertensive retinopathy results from high blood pressure, which causes the retinal blood vessels to become abnormally narrow.

Atherosclerosis of the retinal artery, the same kind of blood vessel blockage that leads to heart attack and stroke, can cause severe damage to the retina.

Retinal vein occlusion is a common cause of blindness. It happens when the central vein or artery of the retina is blocked.